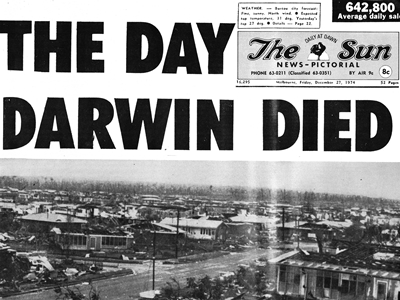

Christmas Day 1974 is forever remembered as the day that Darwin was flattened by Cyclone Tracy.

The destructive winds, measured to 200 km/h before the equipment itself failed, damaged or destroyed virtually every home and building in the tropical city. Seventy one people died and many more were injured.

Much of the city’s 45,000 residents were deemed homeless, leading to a massive evacuation exercise that brought Darwin’s population down to around 10,000 as the extensive clean up and reconstruction of the city was commenced. It would be another three years before Darwin’s population was restored to pre-Tracy numbers as many chose not to return.

The cyclone took out Darwin’s two television stations — ABD6 and NTD8 — and radio stations. ABD6, with the resources of the ABC as the national broadcaster, was able to get transmission restored within days, likewise with ABC’s radio station 8DR. Commercial station NTD8 was less fortunate as it would be another ten months before it was able to renew service.

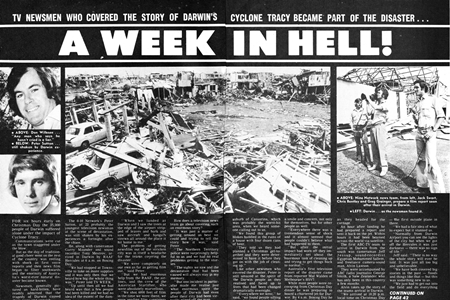

But while Darwin had been devastated on Christmas morning, much of the country remained oblivious to the extent of the disaster until much later in the day. Even news crews making their way to Darwin were unaware just how dire the situation was. Flying in via RAAF Hercules on Boxing Day morning, 0-10 Network reporter Peter Sutton said he and his crew, cameraman Garry Maunder and sound recordist Tony Mestrov, only learned of the significance of the damage when making a stop in Townsville. “It was only then that we heard how big the whole thing was,” he told TV Week. “Up until then all we had heard was that a few people had been killed and we no idea of the extent of the damage When we landed at Darwin and I saw the trees at the edge of the airport stripped of leaves and bark and saw aircraft and hangars strewn all around the place it hit home to me.”

With communications links out of Darwin severely impacted, getting the news to the rest of the country was a challenge. “We were completely on our own as far as getting film out,” Sutton said. “But we had enormous help from the RAAF, the airlines and the crew of the American Starlifter, who were absolutely marvellous. We shot 6000 feet of film in the time we were there, we were sending film cannisters twice a day, and we didn’t lose one.”

The first television report from Darwin came from Mal Walden, then a reporter for HSV7, Melbourne. He had arrived at Darwin via a chartered jet just after 4.00am on Boxing Day. An hour after landing he had prepared a report and sent it back via the jet. Within hours the report had been beamed around the world via satellite. “Naturally it is one of those jobs you never forget, but as a reporting job it wasn’t hard,” he told TV Times years later. “The news was everywhere. All you had to do was point a camera and put a microphone at someone’s mouth and you had a story. The big problem was getting the stories out of Darwin. I’d spend hours trying to get the reels of film on some sort of plane to Melbourne.”

The first ABC crew to arrive in Darwin from the south included cameraman Jeff Jessup, sound recordist Mohammed Sallem and freelance camera-sound man Alvin Lawson. They were accompanied by ABC radio journalist George Smith. “We arrived at 10.20pm on Christmas Day — the first outside plane in there. We had a fair idea of what to expect but it stunned us. Normally from Darwin airport you can see the lights of the city but when we got off the Hercules it was just darkness — there was no sign of life,” Lawson told TV Week. Cameraman Jessup added: “We have both covered big stories in the past — floods and things like that — but this was something new to us. We just had to get out into the field and do everything we could possibly do to get the story out the best way we could.”

Another Seven Network reporter, Don Willesee from Sydney’s ATN7, spent eight days in Darwin and said what he and his crew saw affected them deeply. “Any man who says he hasn’t cried is a liar,” he said. “Like most of the other reporters, I initially slept in the Travelodge, which had remained generally intact. For three nights there was no electricity and the stench was unbearable. We were so exhausted at night that we just flaked out. We had a serious drink problem, there was either warm soft drink, which was very scarce, or warm beer. One day, to stop dehydrating, I drank seven cans of beer. The first at 6am.” Cameraman Nigel Jones had initially been dispatched to Sydney’s Mascot Airport only to film footage of Darwin evacuees arriving in Sydney but he and sound assistant Jack Swart ended up “thumbing a lift” on a Navy plane to Darwin. “I had little money, no toothbrush, one set of clothes and only half my equipment,” he said. “We had a torrid time for the first few days with no food, only warm beer to drink and no washing facilities. My clothes started to fall to pieces. During our eight-day stay I kept vomiting from the stench of rotten food which the police were dragging out of refrigerators.”

Covering the disaster for the Nine Network were reporter Greg Grainger, cameraman Steve Richards and sound assistant Chris Bentley. “We arrived in Darwin early on Boxing Day and started filming. We had practically no sleep. The situation there was unreal,” Grainger said. “The rigours of the tropic weather took its toll. The air was steamy and close and there was little to drink. Everywhere we went there was a story. We were lucky and got hold of some cans of fruit juice to ward off dehydration. We became part of the disaster, being moved around like everyone else. After three days or so we found a swimming pool full of water, which was a relief. We splashed water over our heads which was the best we could do to keep clean. Many times while we were working there the emotion almost overtook me. It was terribly sad.”

Despite the lack of communications, infrastructure and basic facilities, media personnel were praised by the Director-General of the Natural Disasters Organisation for their conduct in what was a very trying and distressing time for the city of Darwin:

“It is to the credit of media representatives in Darwin that they willingly accepted the primitive facilities and cheerfully operated under great difficulties in common with the other citizens of Darwin.”

“The conduct of media representatives located in Darwin reflected great credit on the Fourth Estate.”

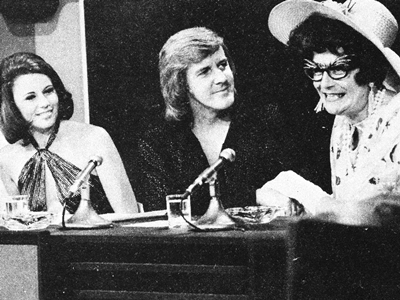

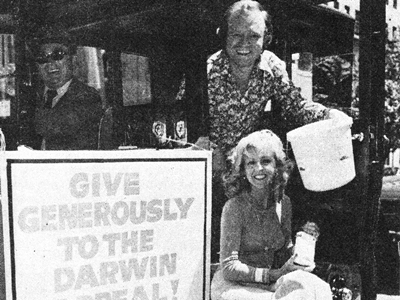

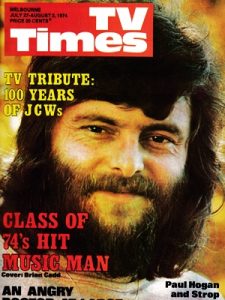

While the newsmen were in Darwin covering the disaster, viewers around the country were being urged to donate to the relief effort. The Nine Network, in association with regional television stations and News Limited newspapers, held a 28-hour national telethon across New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. The telethon required a massive effort by Nine staff, many who were recalled from Christmas holidays, with the technical assistance of the Postmaster-General’s Department and the Overseas Telecommunications Commission. Personalities, sporting identities, politicians and performers from across the country donated their time to the cause — including Barry Humphries (and his close friend Dame Edna Everage), Bert and Patti Newton, Barry Crocker, Little Pattie, Johnny Farnham, Julie Anthony, Col Joye, Reg Lindsay, Lionel Long, Hal Todd, Michael Schildberger, Gerard Kennedy (pictured above with Miss Victoria, Ann Gilding) and The Kinsmen.

While the newsmen were in Darwin covering the disaster, viewers around the country were being urged to donate to the relief effort. The Nine Network, in association with regional television stations and News Limited newspapers, held a 28-hour national telethon across New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. The telethon required a massive effort by Nine staff, many who were recalled from Christmas holidays, with the technical assistance of the Postmaster-General’s Department and the Overseas Telecommunications Commission. Personalities, sporting identities, politicians and performers from across the country donated their time to the cause — including Barry Humphries (and his close friend Dame Edna Everage), Bert and Patti Newton, Barry Crocker, Little Pattie, Johnny Farnham, Julie Anthony, Col Joye, Reg Lindsay, Lionel Long, Hal Todd, Michael Schildberger, Gerard Kennedy (pictured above with Miss Victoria, Ann Gilding) and The Kinsmen.

(Pictured above: Ros Wood, Barry Crocker and Dame Edna Everage; and below, Bert and Patti Newton.)

Appearing via satellite from London were John McCallum, Reg Varney, Keith Michell, Love Thy Neighbour star Kate Williams, Alan Hargreaves and Sandra Harris.

American-born Don Lane, formerly of TCN9 Sydney’s Tonight show but since returned to the US, came back to Australia for the telethon. His return led to an invitation to host a new variety show which became the long-running The Don Lane Show.

Nine Network newsreaders Brian Henderson and Peter Hitchener hosted the telethon with only brief rest periods, while TCN9 sports commentator Ron Casey reported updates from the tally room.

At the end of the 28-hour telethon a total of $3,089,873 had been raised — exceeding Nine’s expected target by $1.5 million.

A month after Cyclone Tracy a Film Australia documentary, When Will The Birds Return?, aired on ABC. Despite the massive amount of news coverage that had already come out of Darwin, the documentary presented to many an unseen depiction of the disaster as the city and its people comes to grips with loss while embarking on cleaning up and reconstruction.

TV Week columnist Eric Scott described it as a “masterful example of disciplined reporting”:

“The film covered every aspect of Darwin as it is today — a town devoid of homes, trees without leaves — and the remaining people stolidly determined to lift the place back up again. The entire documentary left me breathless with admiration for everyone in that tropical town — the local citizens, the imported workers, the police, and the military. It was a story that smacked of quiet heroism in every cyclone-torn street, and, as a documentary, must surely be the best of this or any other time.”

“In years to come maybe some movie company will develop the idea of re-creating Tracy in a big budget film. They will probably make a good job of it, but it could never bring home the message as potently as When Will The Birds Return?”

Over a decade after Scott’s editorial there was a big-budget mini-series, Cyclone Tracy. But more on that tomorrow…

Tonight, at 8.30pm, ABC commemorates the 40th anniversary of Cyclone Tracy with the special Blown Away, promising a different perspective on the disaster, the subsequent reconstruction of Darwin and the long-term legacy of Tracy.

Source: The Sun News Pictorial, 27 December 1974. TV Times, 18 January 1975 TV Week, 8 February 1975. TV Week, 15 February 1975. TV Times, 27 January 1979. Cyclone Tracy

I have a story about the part played by the citizens of Tennant Creek during the exodus from Darwin.

LIONS TO THE RESCUE or THE RETREAT OF THE DARWINIANS

By Henry Broadbent

Forty years have passed since that fateful day when Cyclone Tracey devastated Darwin. Immediately the news reached Tennant Creek the citizens swung into decisive and effective action under the leadership of the Tennant Creek Lions Club led by friend Les Liddel. They organized the townspeople to receive the refugees from Darwin, feed them, clothe them, fuel and repair their shredded vehicles, put money into their pockets or put them on a ‘plane to Alice Springs. The locals did it all with no one looking over their shoulders. Now, forty years later, Les is no longer with us but his wife Alma still keeps his memory bright in Queensland.

I learnt the story when I revisited Tennant Creek to do a job there. From 1966 to 1974 I was the Chief Engineer at Peko Mines N L but left the area in August 1974, some months before Cyclone Tracey. As normal in a mining area Peko Mines supplied the local Township of Tennant Creek with electrical power. Over the years the quantity to ore mined continually increased and from time to time new diesel generators had to be installed. As the population of Tennant Creek grew so did their appetite for power. The town was administered from Darwin but had a local council. Interestingly, the long time local people didn’t care much for air conditioning. Instead they lived in unlined galvanized iron-walled houses which cooled-down quickly at night. However newer dwellings needed air conditioning and power. Typically the Canberra controlled Northern Territory administration built brick and concrete flats suitable for Canberra. The designers evidently had no understanding that the sun shines from the south in summer above the tropic of Capricorn. These flats were purgatory to live in. The houses provided by Peko Mines were also unsuitable, being a Townville type with adjustable louvre glass walls through which the cold winds blew in winter.

About 1973 calculations showed that a new generator would soon be needed – not for processing ore but to supply the town. The manager said that Peko was in the mining business and was not a service industry. A letter was sent to the Northern Territory Administrator to tell him that in future Tennant Creek would have to provide their own power. The new diesel power station was still waiting commissioning in early 1975.

I took my family to Melbourne in late 1974 to enable our children to get their education without being sent away to boarding school and took up employment with Lohning Brothers. Some months before leaving Tennant Creek I had arranged a contract with Lohning Brothers to supply equipment for the power station. As a result, in April 1975 I was sent to Tennant Creek with an electrician to install the equipment in the power station. Unwisely we worked on the live415volt switchboard – the one still supplying Tennant Creek. When my screwdriver slipped and the circuit breaker went up in electrical flames like a blast furnace. I leapt for the isolating switch-button while the electrician grabbed the nearby Freon fire extinguisher that snuffed out the roaring flames like magic. An uncontrolled fire emits far more toxic gases than any Freon extinguisher (it’s not toxic anyway). That the Freons are a cause of the “ozone hole” is one of the late 20th century fairy stories and part of Greenie plan to drive us back to the dark ages. The potassium bicarbonate powder alternative now in use might put out a similar fire but the cleanup of the salt would greatly add to the repair work. The date of this incident was 24th April 1975.

The power station was a galvanized iron shed and hot as Hell. I went back to the motel feeling pretty rotten for more than one reason. I wondered if I had eaten something bad or perhaps had heat stress. As vomiting after lashings of salt water did not work, the motel proprietress, with her preschool child also in her vehicle took me to the new medical centre. I warned her that I might have mumps because my son had contracted it a week or two before. She said that it was better to get such maladies when young anyway. It was mumps and after a few days I left the hospital with instructions not to travel for a few days. That evening I trotted around to visit my friends Les and Alma Liddel. Les was able to tell me what had happened whilst I sweated away in the hospital bed.

The Tennant Creek hotels were left without power to keep their beer cold for most of Anzac Day. Actually I imagine they found auxiliary generators. The new power station was ready to go except for commissioning tests. However, it took all day whilst various members of the N T Administration passed messages between Darwin and The Alice before some brave soul finally took responsibility and told the operators to get the new generators on line and forget about the commissioning tests.

Les showed me a piece of heavy copper bus bar that had been completely melted through. The piece had been souvenired by his electrician son. Mute evidence of the power involved.

Then I listened to the saga of the retreat of the Darwinians from the point of view of the Tennant Creekites. Les at the time was a committee member of the Tennant Creek Lions Club. Late in 1974 three of the committee members met – over a beer no doubt – to discuss what the Club would do in case of an emergency; such as what the Brisbane Lions did when the Brisbane River flooded a year or two previously. On Boxing Day 1974, when the news of Cyclone Tracey came through, Les was the only one of the group left in town – so he was It. Les knew exactly what was about to happen. It would be a repeat of the aftermath of the bombing of Darwin by Nippon in February 1942. Les also knew what to do. First he rang the headquarters of Lions Australia in Newcastle and spoke to the Head Shebang. Paraphrasing his words – “I need money to look after the refugees coming south from Darwin” “How much?”- “$40,000 and I want it today” – “ You’ve got it”.

Now Jack Ford had a garage and was the Ford agent. He knew all the other fuel suppliers too.

Wyn Joswik, local dent knocker, refrigeration mechanic and auto parts supplier, had a shed full of tyres. Les himself, with his wife Alma, had a transport business, was railway agent and was the local bottle gas agent. They knew all the local businessmen, hotels and mines managers. Les said that the Tennant Creek men and women swung into action under the direction of the town leaders. Townsfolk donated their spare clothes, prepared, cooked and served food and drink and for several days worked their butts off. Whatever had to be purchased was bought as required from the local stores.

The refugees arrived in vehicles in all sorts of condition and disrepair. Some cars had been sandblasted to shiny steel and the rubber of the tyres abraded down to the canvas. Many had only the clothes they were wearing when the cyclone hit. Some had only a pair of briefs or pajamas. Few had any money. Vehicles were repaired, re-tyred and re-fueled or retired. The occupants were clothed, fed, watered, rested and given money to tide them over. Many were put on the plane to The Alice. There were even freeloaders detected. These were put on the plane and met by the police at Alice Springs.

All this was done without any outside help from Civil Defense, Red Cross, Salvation Army, The Army, or Federal Government. These organizations were all frozen with no one with authority to spend money and be prepared to help to the refugees. Maybe it was mid-holiday season but really the problem was that no one except the Lions Club Organization had any plans of how to respond to an emergency. Shades of Dubwa President Bush and New Orleans! $40,000 dollars doesn’t sound much these days of hyperinflation but think of the equivalent of, say, $500,000. It was money given freely by the Lions with no intention or prospect of getting it back.

The sequel was a national meeting of service chiefs at Mt Macedon to work out how it was that a service club had been able to act immediately and decisively at Tennant Creek when all other groups were impotent. Les was a guest of honor. They were ready to learn from him. As Les put it – “The Big Wigs stood up one by one and introduced themselves: ‘XXX – Governor General’, ‘XXX-Chief of Federal Police’, etc. etc. Finally I stood up and said: Les Liddel, Private Citizen”.

Hopefully, the next time something like this happens there will be several groups competing for the honors of doing something. And of course at Darwin itself the locals ably took charge and felt very sore that the Federal Government sent someone to take charge in a rather heavy-footed fashion.

My wife Betty and I finally returned to Tennant Creek in October 2000 in time to visit the Liddels a year or so before they had to leave for health reasons. It was as if 25 years had not passed – but the town was very different. Les finally succumbed to his diabetes a year or two ago and is no longer with us. However his wife Alma is still going strong and enjoying the twilight of her life with family in Queensland. It is a privilege to have known a private citizen like Les – who knew what to do and DID IT. I feel more people should know of the part he played in the aftermath of the Darwin cyclone.

For myself I was lucky. When I was able to return to work my employers, who were also friends, said no more about the matter but shuffled me off to do a job outside the firm’s office.

Henry Broadbent

Somers Vic 3927

December 23, 2014

Henry, while I don’t agree with your criticism of the Greenies, who were almost non existent back then, what a terrific account of the time. Thank you for posting your memory.